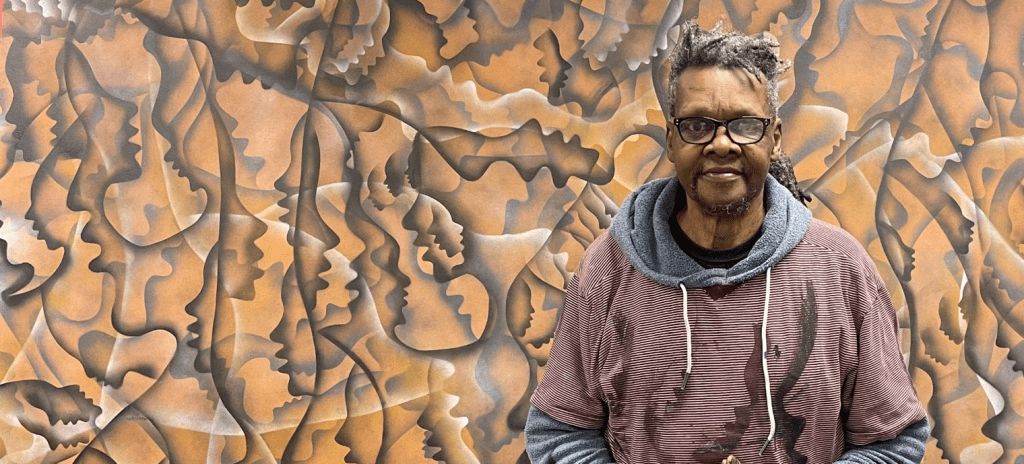

Lonnie Holley is one of those people whose very existence is a bit awkward for the United States of America. He’s a good looking guy, a few months older than my Dad but healthier looking than even me. He’s not some crinkly, confused, 112 year old veteran of the first world war, baring a toothless smile to the camera on the arm of his minder. A minder he needs to remind him to put his underpants on in the morning, and works overtime changing him considering the amount of times each day he pisses himself. He is still plugged in, still 100% articulate, more creatively engaged now aged 73 than he’s ever been. He didn’t become an artist until he was 29. He didn’t even begin releasing music until he was 62. There’s no rush.

Which all means he has pretty vivid memories of being born in Jim Crow era Alabama.

They let me go from Mount Meigs, Alabama

In 1964

But with some cuts and bruises that I will never forget

Alabama Industrial School

The hardships that the children was going through

Children after children after children

Picking cotton

Toting those bales

Bending our backs

Hoeing up and down the ditches and the creeks

Flat weeding

Hearing the old Farmall tractor chucking up the hill…Nobody taught us anything

Mount Meigs

Got no education

Nobody let us have no wisdom

They beat the curiosity out of me

They beat it out of me

They whooped it

They knocked it

They banged it

Slammed it

Damned it

Damned the curiosity

Only going one way down the row and making sure that you kept that row straight

Making sure that you kept that row straight

Mount Meigs, Alabama

Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children

We didn’t get no scholarship

We didn’t get no graduate degree

But all that information is still within me

All of that information

We non-Americans don’t really know or care about the different US states. But we all know that Alabama is the really bad one, don’t we?? If I were born in Alabama to working class parents, decades after Lonnie was, my life would still suck. And I’m white!! I have life on the easy setting – white, male, straight. Kinda disabled, yes, but that was self-inflicted so not sure it counts – and I live in fucking Manchester* – one of those horrible liberal cities that is loudly proud of how many marginalised communities it has, as it shepherds them into ghettos of other low income households and lets landlords and energy companies violate them endlessly without any sort of protection – and I still think my life sucks! Because it does! Because I’m living in latter stage capitalism without any inherited wealth! So you know how serious I’m taking it when I say that Lonnie Holley’s life sucked even more being born a black kid in a state that’s still pretty much a Jim Crow tribute act to this day, but actually during Jim Crow!

(*UK. the proper one)

Holley was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1950, the seventh of twenty seven children. When do people have so many children, to this day? When they don’t expect a decent amount of them to reach adulthood. And a black kid born into Jim Crow USA – especially in the most Jim Crowly state – was living on borrowed time. Holley claims that he was raised by a burlesque dancer until the age of four. That woman had apparently offered to breastfeed him when he was young and just… never gave him back to his birth mother. He was then sold to another family for a pint of whiskey. This might all be some supreme, legend building bullshit on the part of Holley, but considering how often he’s repeated the story I think it’s only fair to at least consider it fact now. The patriarch of this new family was an abusive drunk, so Holley would frequently try and run away. One time when running away he was hit by a car and in a coma – pronounced braindead – for three months. Eventually, aged 12, his third set of parents tired of his constant breakouts, and so sent him to the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children.

It shall be unlawful for a negro and white person to play together or in company with each other in any game of cards or dice, dominoes or checkers

Birmingham, Alabama, 1930.

I know, ‘Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children’ sounds like a lovely place, doesn’t it? It was, unfortunately, not the picnic its title will lead you to believe. Called the ‘Alabama Reform School for Juvenile Negro Law-Breakers’ until 1947, when it was decided that not having committed a crime should be no barrier to prolonged abuse, sexual assault and slavery. It was a canny read of the market: almost all homes for neglected or abandoned children in Alabama were segregated and didn’t allow black kids – Alabama gonna Alabama – so the school in the Mount Meigs community of Montgomery was more than happy to just chuck all the children together. All the black children. Because they were already more than qualified for what the school was planning for them to do.

Because remember when I said that Alabama gonna Alabama?? Yeah, they just used the children as slaves. I’m not talking about ‘neoslavery’ or suggesting that – pretty carelessly given the circumstances – they ‘worked like slaves’. No, actual, forced to work without pay in the fields outside the school, picking vegetables, tending to livestock, literally picking cotton. “At night they went back to dilapidated living quarters and ate measly portions of food from a kitchen former residents said was filled with roaches. One man remembers children so hungry they ate corn out of cow manure”.

People like Holley are awkward presences because they are living, breathing, actual adults in 2023 who can actually remember how recently in American history this all was. Many people who were forced to attend the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children were completely broken by the experience, with many continuing the cycle of violence triggered by such a traumatic formative experience that they’re now in prison, some on death row.

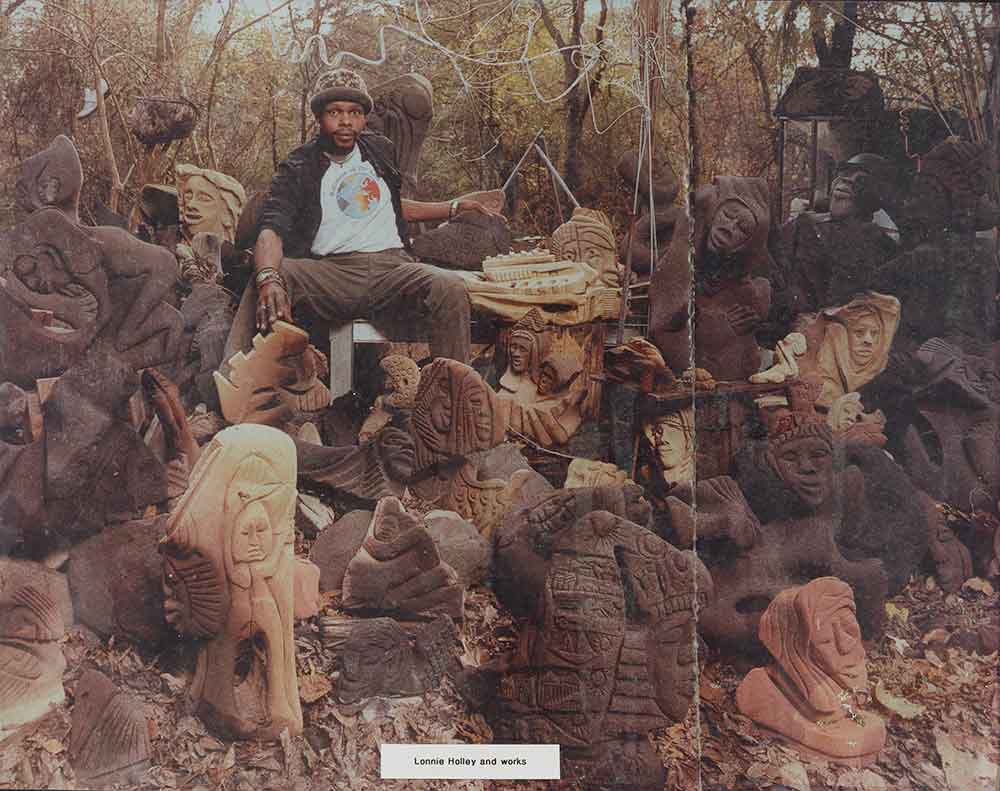

Holley may well have been one of those people, were he not lucky enough to find a different outlet. When he was 28 his sister’s two children died in a fire. The family couldn’t afford to buy any gravestones, so Holley made them himself from sandstone blocks he took from a local foundry:

It was like a spiritual awakening. I had been thrown away as a child, and here I was building something out of unwanted things in memorial of my little nephew and niece. I discovered art as service.

New York Time 21.05.06

Yadda-yadda-yadda, a little over forty years later, here we are with ‘Oh Me Oh My’, an absolutely incredible record that never once sacrifices any artistic leanings but still ends up almost being close to a commercially approachable record. This is hardly Clive Davis pumping up Santana by adding extra Rob Thomases and Dave Matthewses, but a lot of credit has to go to producer Jacknife Lee for managing to reign in Holley’s more extreme and near endless live improvisations into bite size examples and furnishing them with backings that almost make them sound like standard songs. Holley’s outsider art is always present, and the heft of the album undoubtedly comes from his lyrics and their delivery, but there are actual hooks here! I’ve often found myself singing along to lines like “I thought about how grandmama used to be down on her knees/How mama used to not be able to get up off her knees/After giving birth to baby after baby after baby after baby!”. This might sound near heretical, but despite the hardships and the traumas that Holley has been through. ‘Oh Me Oh My’ isn’t meant to be some dark and grim night of the soul, Holley isn’t here to just point fingers at humanity itself for what it has acquiesced. The lasting message of the record is one of unexpected optimism, and many messages of survival and of the power of community are supposed to be sung together:

I need the black ropes of hope

I Can’t Hush

I need the togetherness

Where we put our black hands together and act like a rope

No matter what conditions we have to face

We face them together

I know that there are some that is blind and cannot see And there is some that cannot hear

But we still can feel and we have emotions

We have emotions

We have emotions

We have emotions

We have emotions

We have emotions

3 thoughts on “9 Lonnie Holley: Oh Me Oh My”